Launched in February 2020, Mapping the Gay Guides is an innovative digital history project focused on identifying and mapping the locations listed in the Bob Damron Address Books, a series of travel guides aimed primarily at gay and queer men (and, later to a certain extent, lesbians) that was first published in 1964, and still in publication today. Of particular interest to the project are those guides capturing the period spanning 1964-1980, many of whose listings By associating geographical coordinates with each of these locations, the project aims to “correct our cultural erasure of historical geography,” turning these “incredible textual documents of gay travel guides into accessible visualizations, useful in exploring change in queer communities over time.” Understanding the physicality of queer spaces and the sociability of queer travel and community is an imperative component of any history of 20th century LGBTQ America.

Mapping the Gay Guides is run by Dr. Amanda Regan, Digital Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at Southern Methodist University’s Center for Presidential History, and Dr. Eric Gonzaba, Assistant Professor of American Studies at California State University, Fullerton. Both 2019 graduates of George Mason University, Regan and Gonzaba were involved with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media during their studies, and the project site certainly reflects their enthusiastic embrasure of blending historical archival research and digital visualization tools. In addition to his work on Mapping the Gay Guides, Gonzaba is also the founder of Wearing Gay History, a digital archiving project “documenting the history of modern LGBT communities through t-shirts,” which was recognized as the top student project of 2016 by the National Council on Public History.

While the Damron guides themselves are already a rich archival resource – as Regan and Gonzaba note in the project’s introductory page, the “vast majority of the listings within the first two decades of the guidebooks’ publication are no longer in existence” – the formulation of a digital mapping project opens up opportunities not only for historians or scholars researching queer existence during this period, but also for public history practitioners, museum and historical society programming officers & docents, and tour guides from cities and towns included in the guides’ listings.

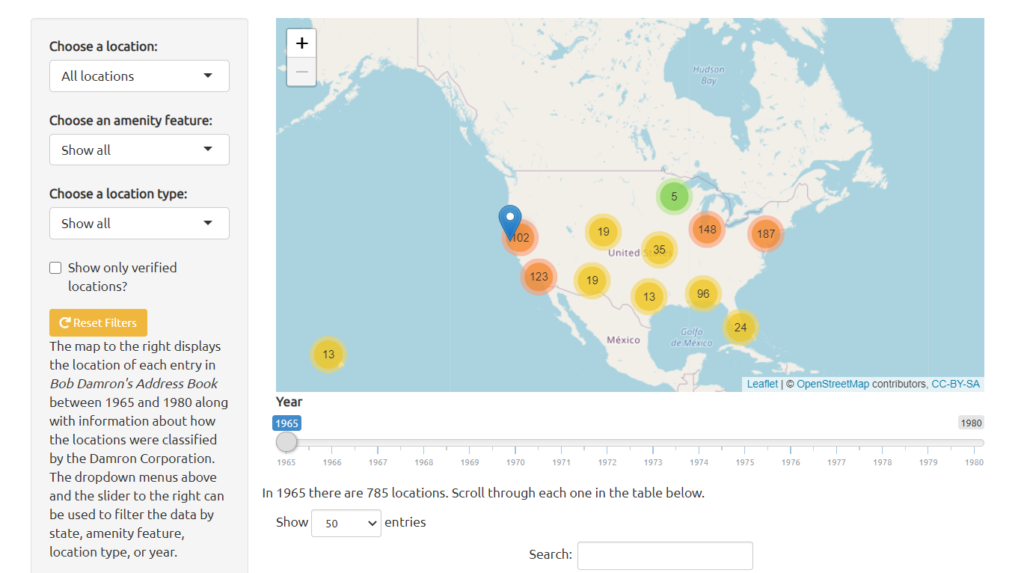

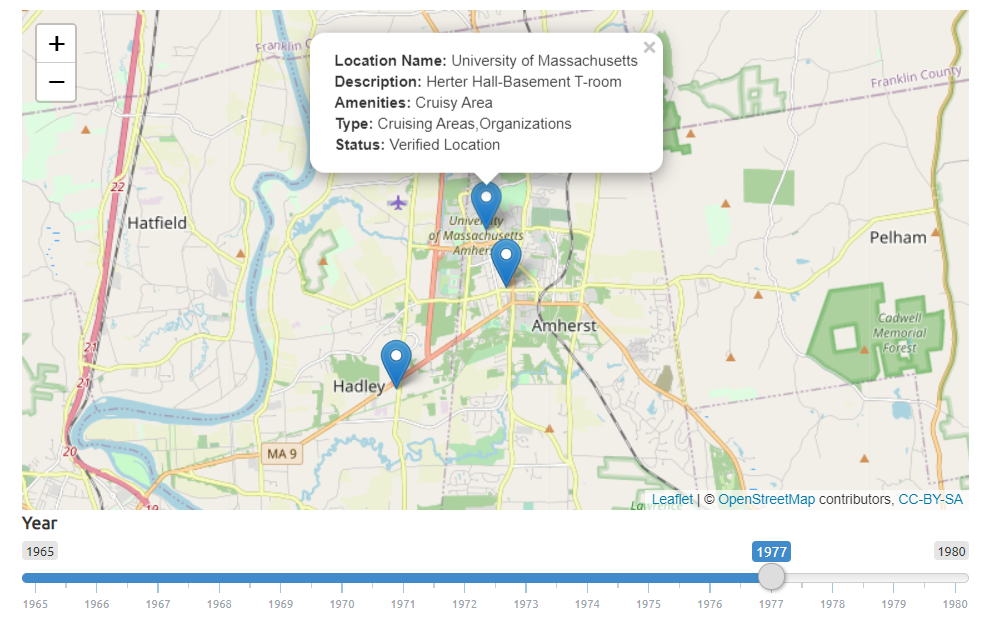

The map visualization itself is crisp and straightforward to use, featuring counted clusters of locations (conveniently color-coded by density within an area) displayed through OpenStreetMap, an open-license web-based mapping tool hosted through University College London, and Leaflet, an “open-source JavaScript library for mobile-friendly interactive maps”. Below the map window is a searchable table listing the dataset used for the project, each with an accumulated set of metadata including a location’s name, the year it was listed in the guide, a description, the street address [if applicable], city and state, “Amenity Features” (Damron’s own list of descriptive categories), type, and status (whether the location has been verified through Google’s Geocoding API). Users can search the map, the table (and accompanying search bar), or a drop down menu, where locations can be filtered by state, amenity feature, or location type (bars, cruising areas, bookshops, etc.). For those wanting a more guided experience, a Vignettes page offers a series of articles that provide additional narrative and context for seven featured localities.

Out of curiosity, I wanted to see what locations here in the Happy Valley made Damron’s lists, especially considering Northampton’s reputation as the “Lesbian Capital of the United States” (WLW culture & gossip mainstay Autostraddle lists the 2012 “queer per capita” at 40.31 same-sex couples per 1,000 households; funnily enough I am actually in the background of the image used in that source!). Unfortunately, listings are rather sparse, most likely due to the guides’ focus on gay male spaces, rather than those frequented by lesbians and other queer women. However, it was exciting to discover that the UMass History Department’s own Herter Hall made it into the 1977 guide, as the basement was apparently a great spot for cruising!

Beyond the map and dataset (compiled by transcribing scans of the guides into machine-readable text and populating the metadata columns), Mapping the Gay Guides also provides a wonderfully transparent model for a successful and self-contained digital history project. In addition to the standard navigation headers of “About,” “Map,” and “Vignettes,” the site also includes a Methodology page describing both the project’s approach to creating the dataset and a descriptive explanation of Damron’s Amenity Features. These features include categories familiar to the guidebook genre (an asterisk denotes “Very Popular,” restaurants are noted by an R, entertainment by an E, and so on) and some that are decidedly more esoteric – for instance, AYOR stands for “At Your Own Risk – Dangerous – Usually Fuzz,” a descriptor that highlights the very real threats of police (and state) persecution and violence that queer individuals faced for existing in public. The transparency continues with the goals and purpose of the project articulated in A Statement on Ethics, as well as the datasets (formatted as raw .csv files) and code for the project, which are openly available on GitHub.